Jessica Dexheimer

April 10, 2009

Fjolla Berisha came of age in a war zone.

She grew up in Kosovo, just outside the capital city of Pristina. Her childhood was comfortable; her father was a businessman and her mother a teacher, and Berisha and her two brothers had many friends in their close-knit neighborhood.

“We had a pretty normal life,” Berisha said. “We were just a normal family, we weren’t very involved with politics or anything like that. We weren’t looking for trouble, but somehow, the worst happened to us.”

In 1996, tensions between Kosovo’s Serbian majority and the Albanian population came to a head. Violence increased, and by 1999, Berisha’s life was forever changed.

“It was so dangerous,” said Berisha, an ethnic Albanian. “The Serbians bombed our neighborhood schools. It did not matter to them about the lives of the teachers, the students inside. They would kill the boys and rape the girls. Every day, it was a danger to leave our house.”

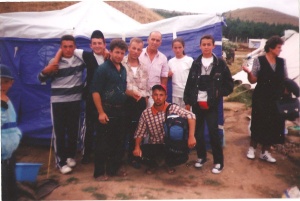

In April 1999, Berisha’s family escaped to Macedonia. Here, they settled in a United Nations-run refugee camp.

Fjolla (rear) lived with her family in a refugee camp in Macedonia for two months before being accepted as a refugee in the United States.

“The living conditions were horrible,” said Berisha. “They had started these programs where you signed up and said you wanted to go to a safe country and find a home. We signed up.”

After two months in the refugee camp, Berisha’s family found out that they had been granted refugee status and were being resettled in the United States.

“We had no idea what was going on,” Berisha said. “We were told we were going to America, and that was pretty much it. We felt lost, but we thought anything could be better than the camp.”

On June 24, 1999, the Berisha family arrived at the Raleigh-Durham airport in their new home of North Carolina.

Coming to America

The Berisha family is not alone. Every year, thousands of refugees are admitted to the United States: in 2007, 54,942 refugees entered the country and approximately 4 percent were resettled in North Carolina. The majority of these refugees are placed in Buncombe, Craven, Guilford, Mecklenburg and Wake counties where they receive help in starting their new lives.

“Whenever a refugee comes to the United States – or any developed host country, really – they obviously need help assimilating,” explained Miriam Kessel, a case manager at the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants field office in Raleigh. “That’s why VOLAGs are so important, they help immensely in those first few weeks.”

The term “VOLAG” refers to ten United States voluntary agencies that work with the State Department to provide resettlement services for newly arrived refugees.

The North Carolina Division of Social Services currently recognizes five VOLAGs in North Carolina: Catholic Social Services, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the Interfaith Refugee Ministry, Lutheran Family Services and World Relief Refugee Services.

These agencies rely on self-generated income and funding from the State Department to provide refugees with crucial services, including cash assistance, food stamps, Medicaid, transportation, job preparation and social adjustment services. They also pay for three to six months of rent and utility bills for each family.

These agencies rely on self-generated income and funding from the State Department to provide refugees with crucial services, including cash assistance, food stamps, Medicaid, transportation, job preparation and social adjustment services. They also pay for three to six months of rent and utility bills for each family.

“The ultimate goal is to help these refugees become self-sufficient as quickly as possible,” said Kessel. “They are guaranteed assistance for six months following arrival, and ideally, by that time they will be able to navigate the American culture and can provide for themselves and their families.”

‘You might as well do a good job.’

Although all the agencies are required to provide certain services, the quality of service that they provide varies widely.

Berisha’s family was assisted by World Relief. The High Point-based organization met the family at the airport, and after a brief cultural orientation, showed them to their new home.

“The house looked like it had been in a war,” recalled Berisha. “There was no furniture, holes in the wall. The water only worked sometimes. We were like, ‘give us a tent. Give us tickets and we’ll go back home.’ We were refugees, but we deserved better than that.”

After two weeks, World Relief found a church in Burlington that was willing to host the family. After the family moved to Burlington, they had no follow-up contact with World Relief.

Berisha thinks that the VOLAG could have done more.

“I do hear cases where some people had everything ready when they came,” she said. “But for us, they didn’t have it ready. We were already depressed and lost, and having to come here to where nothing was prepared, it was really bad. If you’re going to take on the responsibility of helping people like us, you might as well do a good job.”

Jassem Altaie, a 24-year-old Iraqi refugee, had a more positive experience with the VOLAG that helped him and his family.

When Altaie arrived in North Carolina in June of 2008, he was aided by Lutheran Family Services (LFS), a VOLAG from Greensboro.

Altaie’s family left Iraq in 2006 after his father, a translator who worked with the United States military, was shot six times by an anonymous gunman. Fearing for their own safety, Altaie, his mother and grandmother escaped to Jordan, where they lived until they were resettled in the United States in 2008.

“The way we lived in Jordan was not desirable,” he said. “The Jordanians were not exactly welcoming. We couldn’t work. We had no money. We lived with another family in an apartment with only two rooms. So, when we came to Greensboro, life was good.”

In Greensboro, LFS placed the family in a modest townhouse and helped Altaie enroll at Guilford Technical Community College.

“It seemed as if everyone from LFS wanted us to succeed,” he said. “They have things that they are required to do for every refugee, but they did more than that. They did everything to make us feel welcome and happy with our new lives.”

Tara Greenlee, Altaie’s case manager, said that all VOLAGs are similar in the services that they provide for refugees, but the quality of services is dependent on the individual’s case manager.

“Honestly, we receive the same amount of funding as any other organization in North Carolina, and we provide the same services,” she said. “It is more of an issue of the individual case manager, if they are overworked or if they have time to devote to each refugee.”

Some refugees who come to the United States are ‘sponsored’ by friends or family members who already live in the country.

Alee Lwamba Saltzmann, 38, a Rwandan refugee, arrived in United States in 1997 and lived with her uncle’s family in Winston-Salem until she saved enough money to support herself.

In cases such as Saltzmann’s, Kessel said that the state has “minimal intervention” with the refugee and provides only the most basic financial and medical services and asks the anchor families to help orient the new arrival.

Balancing both cultures

Refugees are forced to adapt to a new culture immediately upon arriving in the country.

“If you’ve ever been in an airport, imagine getting out of that airport without being able to read any of the signs or ask anyone for help,” said Bonnie Harvey, an Elon University senior who has volunteered extensively with refugees for six years. “If not knowing the language is bad enough, imagine being surrounded by all sorts of foreign technology. That’s exactly what refugees go through when they first arrive in the States, and some of them have the added dilemma of not knowing basic concepts of how to wait in line or respect personal space.”

Harvey added that she once worked with a group of refugees that was lost in an Atlanta airport for more than eight hours.

However, the problems that refugees face do not end at the airport. Although some refugees learned English in school or through aid workers at the refugee camps, far more need help learning basic English phrases.

Altaie was fluent in English before arriving to the United States, but neither Saltzmann nor Berisha spoke the language and had to rely on innovative ways to learn it. Both women said that they watched hours of American television and would listen in on conversations between native American speakers.

Saltzmann used creative ways to learn the language.

“In Rwanda, we spoke Bantu [tribal] languages but I also spoke French,” she explained. “They don’t make dictionaries to translate Bantu to English, but they do make French to English dictionaries. So, I bought the English lessons that they make for French children and taught myself the language through that way.”

She said that within six months she was fluent; Berisha said that she was fluent after four months.

Once refugees master the English language, they must focus on assimilating with the American culture.

“The littlest things can make you stand out,” said Altaie. “I remember how when I first arrived, I tried to imitate the American men that I saw in movies and on television – loud and always joking and flirting. It was obvious that I was trying to be something I wasn’t and that made me stand out more.”

Greenlee said that most VOLAGs offer classes designed to help refugees fit in with the American culture. The classes cover a variety of topics including personal hygiene, American slang and making social plans.

However, some refugees are hesitant to participate in the classes.

Altaie said that his mother and grandmother have not taken any of the classes provided by LFS.

“You have to understand that refugees walk with one foot in two cultures,” he said. “We have to deal with fitting in in American culture because we have to, but we still want to remain true to the country where we were raised … We left because we had to, not because we no longer cared for our homeland.”

Working hard for a new life

Before arriving in the United States, refugees are extensively screened by the Department of Homeland Security and are eligible to work immediately upon arrival. Within two weeks, they are given Social Security cards and any necessary vaccinations and are encouraged to start looking for jobs soon after.

Each VOLAG assists the refugee with securing a job and provides pre-employment training. According to the N.C. Division of Social Services, working refugees start with an average hourly wage of $8.29.

For some, any employment is welcome.

“When I first arrived in Winston-Salem, I was definitely suffering from what you might call post traumatic stress disorder,” said Saltzmann, who lived in a refugee camp in Zaire for three years before moving to the United States. “All day long, I would sit in my uncle’s house and think about horrible things that happened in Rwanda. I felt sorry for myself. When I started to work [in a nursing home cafeteria], the work was easy and I was able to think of other things. I was able to forget for a little while.”

For others, menial labor for little more than minimum wage was accompanied by an unwelcome decrease in status. It can also be a new experience for women and teenagers who would not have been allowed to work in their home countries.

“For my parents, [the resettlement experience] was an absolute horror,” said Berisha. “It was very, very challenging. You have to understand that they were both educated and successful in Kosovo, but in America, they were working bad jobs and not getting respect.”

In Kosovo, Berisha’s parents had both worked; her mother as a teacher at a prestigious private school and her father as a successful businessman. In the United States, their first jobs were as cashiers at a convenience store and a gas station, respectively.

“It was difficult for them because they had literally spent their whole lives in Kosovo working hard to get educations and further their careers, and all that was wasted in a dead-end job,” Berisha said. “The worst part was the lack of respect from customers and co-workers. They thought, here are these people who don’t speak English, working in a gas station, they must not be very smart.”

Harvey said that in her experience, VOLAGs try to place refugees in jobs for which they are qualified. Sometimes, refugees have little formal education but may be skilled in a trade like sewing, woodworking or cosmetology. Ideally, caseworkers try to capitalize on these skills and build a career, but they often run in to the problem of a lack of funds.

“Basically, the refugees have the skills but not the money to buy a sewing machine or open a shop or whatever,” explained Harvey. “So, it’s back to some low paying, dead end job.”

“Basically, the refugees have the skills but not the money to buy a sewing machine or open a shop or whatever,” explained Harvey. “So, it’s back to some low paying, dead end job.”

However, plenty of refugees are able to build careers. Saltzmann makes an admirable salary as a high school French teacher; Altaie hopes to succeed with his anticipated degree in Computer Information Systems.

Learning to succeed

As caseworkers help adult refugees to find jobs, they also place the children in schools.

Public schools present students with a new world, new opportunities but also new challenges.

Grade level is determined by age, not by test scores, and as Harvey explained, this can lead to “16-year-olds in high school who cannot read or write at all.”

Harvey works at a Greensboro community center that is sponsored by AmeriCorps and the North Carolina African Services Coalition. Here, she works with refugee youth and plans after-school programs, tutoring sessions and reading workshops. She said that these services are especially crucial in cities and other areas where overworked teachers do not have the time or resources to spend in assisting struggling refugee students.

Far too often, a student’s academic struggles lead to emotional struggles.

“In Kosovo, I was happy, I had friends and I actually liked going to school,” recalls Berisha. “When I started seventh grade [in Burlington], I was lost and depressed. I didn’t connect with any of the kids and I didn’t understand most of the things people said to me.”

Harvey acknowledged that all students react to stress differently, but said that she has noticed general trends in the behavior of refugee youth.

“Normally, they’re the quiet kid in the back of the classroom who is doing their best not to get noticed,” she said. “Occasionally, we do see refugee youth who act out. They won’t calm down in class, or in worst case scenarios, they’re violent towards other kids.”

For the most part, though, Harvey said that most students seem eager to learn and participate.

Altaie, for one, was grateful for the educational opportunities.

“What happened to us in Iraq was awful,” he said. “But I am happy that it brought me here to the United States, to all this great technology and teachers that I could never have had back home.”

Trying times

The recent economic slump has led to even more struggles for refugees.

Many job prospects have vanished, and funding for VOLAGs and other support groups has slowed.

Although Greenlee could offer no specific figures on how much the economy has affected the budget for LFS, she estimated that the organization is currently operating on a budget that is 20 percent less than that of previous years. She said that she thinks this decrease has been standard for most VOLAGs.

Omer Omer, the director of the North Carolina African Services Coalition, a Greensboro-based organization that aids in the resettlement process, said via email that the economy is “by far the biggest problem that refugees will face in 2009.”

He said that the poor economy has led not only to a decrease in jobs but also a decrease in the amount of medical and cash assistance that the government has to offer. He also noted that the poor economy might also lead to a decrease in the number of refugees who are admitted to the country.

Saltzmann, for one, has remained optimistic.

“Of course this year will be difficult for many refugee organizations,” she said. “But keep in mind, most of us refugees come from countries with very little … We have already survived the worst things the world threw at us, we can make it through this just fine.”